Type Driven Development - Scaling Safely with Python

Introduction

Python is a great language. The syntax is readable and allows pseudocode to be converted into code nearly verbatim. While this is great for prototyping and moving fast, scaling can become an issue. One of the issues is with regards to documentation. In statically typed languages, even if there's no documentation, types help provide some sort of documentation that allow new contributors as well current developers to remember where they left off and what their code does. There are ways around this using docstrings as well as unit tests. However, this often involves performing tasks outside of writing code which can be time consuming. In Python 3.5, type hints or optional static typing are allowed and tools like mypy help write safer, more scalable code. The best part is, if the code already has docstrings and unit tests, optional static typing adds an additional layer of safety and documentation to existing projects. This writeup explores practices for documenting and developing scalable Python code as well as illustrating how to use optional static types and type checkers.

Prerequisites

This writeup assumes that Python 3.5 or greater is being used and both mypy and pytest packages are installed. To install them using pip we can type the following command in the shell:

pip install pytest mypy

Docstrings

PEP 257 provides a great overview of what docstrings are and how to use them. The summarized version of it is a string literal in classes and functions that allows developers to document logic, inputs and outputs of those particular sections of code. Below are examples of code with and without docstrings:

No Docstring

def combine(a,b):

return a + b

With Docstring

def combine(a,b):

"""

Returns the sum of two numbers

Keyword arguments:

a -- the first number

b -- the second number

Returns:

Sum of a and b

"""

return a + b

As we can see, the string literal or docstring allows individuals who are looking at the code for the first time as well as someone who worked on it and has forgotten the logic of a program to easily decipher what the code does.

Something else to notice is the function name. In this case, the logic is relatively simple and the name may make some sense at the time of writing the code. However, this simple logic is dangerous. Without knowing what is expected as input and output, there's not a clear way of knowing what this code should do. For example, someone might try to run the undocumented version of this function with parameter a having the value 'Hello' and b with the value 'World'. The function would not throw any errors and return 'HelloWorld' as a result. However, if we look at the intented logic as well as expected input and output provided by the docstring, we'd know that a and b are both supposed to be numerical values, not strings or any other type.

It's clear that writing a docstring can become tedious and take up a substantial amount of time as a project grows. However, the benefits are reaped when extending the code and using it in production because more time is spent being productive rather than figuring out what the code should do and whether it's being done correctly. Docstrings however are not a panacea since there is no way to enforce what is documented in the code and serves as more of an FYI for developers using and extending the code.

Unit Testing

One way to prevent code from being misused is by writing tests. By writing unit tests and making sure that they pass, developers can test edge cases such as passing a string and immediately getting feedback through failing tests. Here's an example of what a unit test would look like for the combine function written above.

In the file main.py, we can write the logic for our combine function. However, keeping in mind the docstring, we might want to add some exception handling.

"""

Module Containing Logic

"""

def combine(a,b):

"""

Returns the sum of two numbers

Keyword arguments:

a -- the first number

b -- the second number

Returns:

Sum of a and b

"""

if(type(a) == str or type(b) == str)

return a + b

else:

raise TypeError

In another file called test_main.py, we can write our tests. Our test file will look like the code below:

import pytest

from main import combine

testparams = [(1,2,3),(2,4,6)]

@pytest.mark.parametrize("a,b,expected",testparams)

def test_combine(a,b,expected):

assert combine(a,b) == expected

testparams = [('a','b'),('a','b')]

@pytest.mark.parametrize("a,b",testparams)

def test_combine_exception(a,b):

with pytest.raises(TypeError):

combine(a,b)

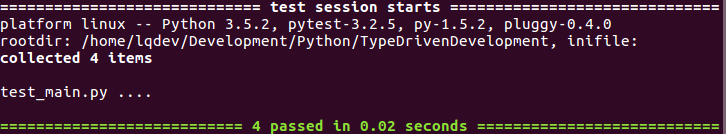

In our shell we can enter the pytest command inside of our project directory and get the following output.

pytest

The results from pytest ensure that passing the expected parameters returns the expected output which is the sum of two numbers and passing in the wrong parameters such as those of type string return a TypeError. This gets us closer to where we want to be where we're able to test whether the functionality of our application does what it's supposed to. Like docstrings, there is additional work and time that needs to be accounted for when writing tests. However, this is a practice that should be taking place already and in the case of Python which does not provide the type checking or compilation is a way to if not ensure that our logic is sound, at least it provides us with an additional form of documentation and peace of mind that the code is being used accurately.

Type Hints (Optional Static Types)

Good practice would have us write docstrings to document our code and unit tests to ensure the soundness of our logic and code. However, what if that seems like too much work or there's not much time to perform those tasks. Is there a shorthand way that we can both document our code for posterity as well as ensure that we can only use the code as intended. That's where type hints comes in and starting with Python 3.5 have been accepted by the Python community per PEP 484. With type hints our code would not change much and with a few extra characters, we can write safer code. Our combine function from previous examples would look as follows with type hints:

def combine(a:float,b:float) -> float:

return a + b

If we run this, it should run as expected given the appropriate parameters. That being said, as with the undocumented example, if we pass in parameters 'Hello' and 'World', it should work as well and we get the result 'HelloWorld'. If we still don't get the result we want and our code is still unsafe, then what's the point? One of the benefits is the documentation piece. In the event that we had no docstring, we could still tell that a and b are both of type float and return a float. The second benefit comes from the use of mypy, a type checker for Python. To see it in action, we can create a script called mainmypy.py and add the following code:

def combine(a:float,b:float) -> float:

return a + b

combine(1,2)

combine('Hello','World')

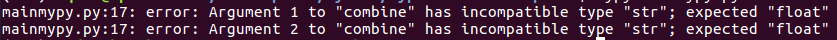

In the shell, we can then use the mypy command on our script to check types.

mypy mainmypy.py

The output is the following:

As we can see, without having to run our code, mypy checks the types and throws errors that we would not have found unless we ran our code. Therefore, we get both documentation by defining the types of parameters and outputs we expect which make it easier for individuals using or writing code to safely do so without having to write long, descriptive docstrings. With mypy, we enforce the good use of code by checking that the correct parameters are being passed in and the correct results are being returned prior to runtime making it safe to scale and write correct code most of the time.

Conclusion

Python is a very expressive language that allows applications to be prototyped in no time. However, the tradeoff is that writing new code or returning to it at a later time without documenting it, particularly the types needed by functions or classes to produce an accurate result can be unsafe. Some existing practices such as docstrings and unit tests can help with documenting and writing safe code. However, tools like mypy and the recently introduced type hints achieve what both docstrings and unit tests do in less time and code. This is not to say that these tools are perfect and ideally, unit tests, docstrings and type hints are all integrated to make developers more productive and create safe, scalable code. Happy coding!